Curtsy Lunge, Yay or Nay?

Let us talk about the curtsy lunge.

Is it bad? Could it be used safely? What are the pros and cons?

Here at MO|RE our opinion is yes, no and let us find out together!

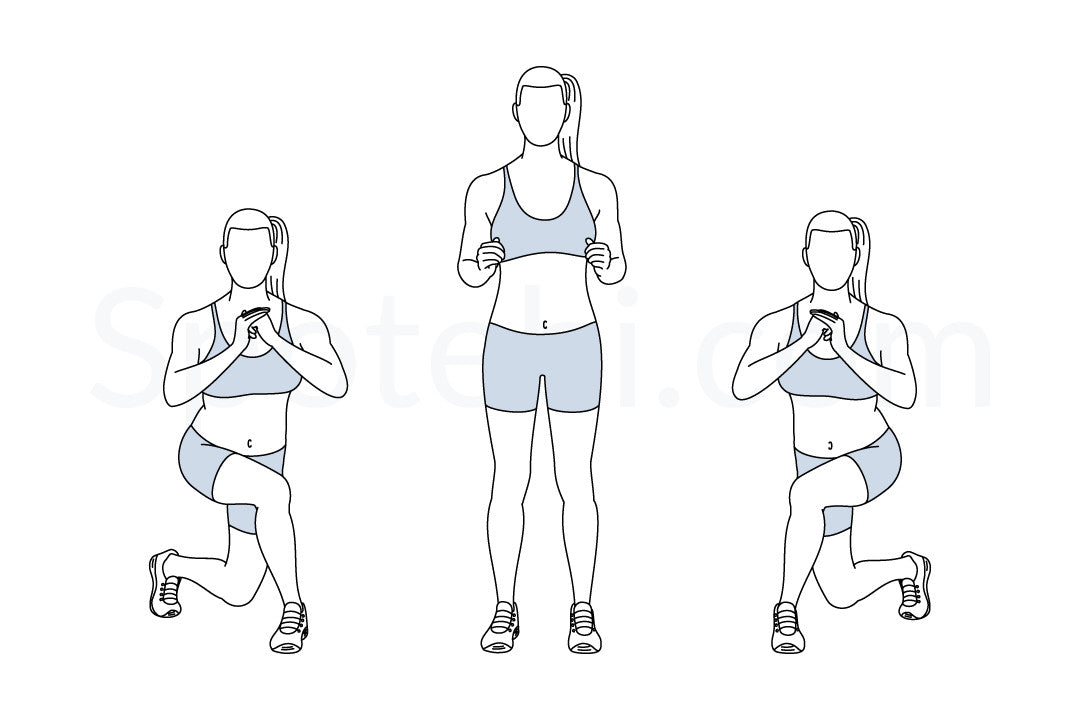

What is a curtsy lunge? This picture shows what it is.

Seems harmless enough, you have probably seen it being done in your local gym or social media channels. However, upon reading the descriptions, definitions and recommendations of the exercise on google, which is most people’s go to when researching a good exercise, you will read some controversial reviews. Let us read what we found and break them down.

The Curtsy Lunge is a great exercise to stabilize* your hips. The movement is a variant of a standard lunge, but you hold your lower body in the position of a curtsy for additional glute strengthening**

*Regular lunges do that, and progressions exist that don’t require the curtsy move.

** Additional how? And furthermore, is this addition worth the potentially big risks that doing a curtsy lunge may provide?

We need to ask these questions when reading exercise recommendations. We need to ask ourselves, why is this fancy exercise better than a plain old tried and true?

The curtsy lunge is an effective, functional, and compound exercise that hits your quadriceps* and glutes. If you are looking to sculpt a curvaceous butt** or to strengthen your thighs***, then this variation of a lunge is your best bet. Lunges**** are a staple for building a strong and toned lower body*****.

*Lunges, if done properly, should work hamstrings and glutes. Lunges are not a quad dominant exercise.

** Glute shape is hugely influenced by genetics, training will maximise your ability to develop what your body is genetically made for

*** Again, not a front leg exercise.

**** Lunges are an AMAZING exercise, but are curtsy lunges?

***** Strong yes, toned depends hugely on other factors and not only on exercise selection.

So let’s start off on the basis that the curtsy lunge is not deemed by us as a viable and a low injury risk exercise, we must ask ourselves why.

We then must assume that the argument will turn towards what if it was used in a controlled environment to strengthen range of safe motion and get the body used to being in that 'exposed' position could it build strength and reduce the chance of injury.

So lets tackle the why is the curtsy lunge not safe. When doing a curtsy lunge, your femur (thigh bone) and tibia (shin bone) rotate upon the patella, which can cause the femoral condyle to 'slice' the ACL.

The LFC would thus potentially slice through the ACL while doing a curtsy lunge, as in order to accommodate that twisting upon its axis would require the LFC to move across sideways onto stationary ACL

So now that we establish the mechanical hazard of the movement, the argument continues to how do you know how far is too far. How far would you rotate before the Femoral Condyle 'slices' the ACL. Our way of thinking is that correct training of the primal movement patterns* and strengthening of the hamstrings will reduce the risk of that rotation happening in the first place!

*that’s the next blogs content!! But the PMP are 7; Lunge Squat Hinge Pull Push Twist Gait

Claiming that putting joints in further ranges can strengthen them is a fairly common argument. Training the muscles in a range of motion beyond their normal range will cause them to fire later in that range, exposing the ligaments to stress they are not designed to handle without the muscles contribution. Ligaments put under prolonged or repeated tensions experience “load relaxation” and creep. They don’t get tighter and stronger like muscles and creep reduces the tensile strength of the ligament. To simplify it, ligaments once overstretched will not retain or return to their previous form.

Besides that, one would be correct about questioning the “controlled situation”. How can we possibly define the exact load and degrees of femoral rotation to ensure we are strengthening the muscles without inducing the load relaxation phenomenon or creep.

The mechanics of material properties of ligaments simply don’t respond to tensile loading the way muscles do.

It is only when we understand stress-strain curves and the responses of the material properties of viscoelastic materials can we see that these particular ligaments don’t behave in that manner. If this sounds very confusing and complicated, it is because it is. However, we just wanted to illustrate that there has been a lot of scientific research to support this argument.

So, with all this said, should you do one? The answer is do whatever you want! If it makes you happy have at it, all we have done here is tried to give you a scientifically accurate assessment of a movement that is largely unknown. Some people often try to level up and do some extreme exercises whilst searching for that elusive edge. The truth is, often, the tried and true basics will get you to your goals in as safe a manner as possible. With the information provided, one might want to stay clear of an exercise that proves to cause more damage than benefits.

Maybe you are super far away from an injury or maybe you are ten bad repetitions away from one. What if those ten reps manifest themselves in a missed step on a sidewalk, or on a hike, something that would otherwise be less damaging had the ligaments not been pre damaged? Let's leave with this thought, you may be 10,000 repetitions away from an injury or you may be 10 reps away from an injury, is it worth finding out how many?